Recording worship

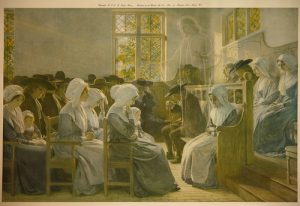

We’re going off-book this time, because we felt like it. There’s a taboo on recording worship during waiting worship. This is especially the case with photography.

This comes up most in regard to Quaker weddings. In non-Quaker weddings, it’s really common to have photography all throughout the wedding. Non-Quakers couples often have photos of themselves standing up front together exchanging vows. For a lot of us, though, we only have photos taken after the wedding is over. Flash photography would obviously be disruptive. That’s a pretty new technological problem. Theologically, some would argue that you can’t capture the Spirit on camera.

Passively recording worship

But recording worship in the sense of recording the content has historical precedent. Shorthand stenographers recorded the messages given in worship sometimes, especially when there was a well-known traveling minister. This may have been controversial, especially around the time of schisms. If the transcript is wrong either intentionally or unintentionally, that opens a huge can of worms. And having those recordings makes it easy to use someone’s words against them. Some of these sermons have been published in books.

Recording worship passively (unlike photography) is less disruptive and so more acceptable. Especially when well-known ministers are present at large gatherings, an audio recorder may be turned on in advance and allowed to run. For regular meetings, some people could be unfaithful to their leadings to speak, out of essentially stage fright with the recording.

We go on a bit of a tangent. Micah makes a point that in addition to there being people who are known for having the gift of ministry, there’s also preparation. What does it mean for a message to be prepared? D months or years of Bible study and prayer count as preparation? Does a concern weighing on a person for months count as preparation? Someone can speak extemporaneously about a topic to which they’ve given much study, thought, and prayer. Mackenzie points out how language changes and that “immediate” used to mean “unmediated” not “fast.” That changes what it means for early Friends to write about “immediate promptings.”

Accessibility & Language

Photography can be disruptive in two ways. There’s the basic one of someone moving around. But there’s also that meeting for worship is full-participation. We’re supposed to be all in unity with the Spirit together.

We wonder if that idea might affect how meetings handle accessibility. A member of the meeting participating in worship and periodically interpreting into sign language might be perceived differently than a hired interpreter who is not participating. Or maybe the latter just costs money, and meetings don’t want to spend it.

Some meetings will also have someone “recording” with a keyboard to a computer screen as messages are given. The text isn’t saved for later, but it’s displayed for Deaf and Hard of Hearing participants. (That’s CART: Computer Assisted Real-Time Captioning.)

In international Quaker gatherings, there’s often simultaneous interpretation for different spoken languages. That’s really difficult when the speech is off-the-cuff.

And on a related note: if anyone wants to translate our transcripts into Spanish or another language, that would be amazing! Also, if anyone wants to toss a few more dollars at our Patreon, so that we can get more of the old episodes transcribed, that would also be fantastic.

References

Transcript

Mackenzie: Hi. Welcome back to Quaker faith and podcast with your hosts Mackenzie and Micah. And since we were just chatting about it, we’ve decided we’re going to do an episode on the taboo on photography recording that exists around waiting worship.

Micah: Yeah. It’s interesting. For me, growing up, when I was a little kid, I think I’ve been over my background before in previous episodes but just as a reminder, I grew up as a small child the son of two Quaker pastors, and this was in a, sort of what I would call a more traditionalist evangelical Quaker church, and by traditional I mean, for Quaker to be traditionalist is to hold to more of the old forms. It’s not necessarily any other kind of conservatism.

But our church held to some of the old forms, including in our service, we would have a time of waiting worship, for like, depending on the day. It would be maybe five to ten minutes. As a young child, I experienced waiting worship on a regular basis and I just sort of picked up, as Quakers say through osmosis, certain, certain things about it. One of the things I picked up about waiting worship was that it was taboo to do sort of active recording activities. In particular, it was taboo to take pictures, to pull out a camera and start taking pictures of the service or even worse taking pictures of someone who was speaking in the meeting for worship.

Mackenzie: Whereas, I got told this one explicitly because I’d been going to meetings for like six months or something, when I went to a wedding, which actually Micah was at that wedding. It was made explicit there. You do not take photos during the wedding and the reason given was, the reason that I understood is that you can’t get a picture of the Spirit being there, and so it’s not, like you’re not really going to capture the experience of what’s going on, so sort of don’t try. But there’s also like, that’s really disruptive, if somebody’s like, especially if there’s a flash on the camera.

Micah: Yeah. When my wife and I got married, we got married in a traditional Quaker wedding so the whole thing, the whole wedding ceremony you might say, was an hour long meeting for worship that was based in silence. We stood up, when we were ready we stood up out of the silence and said our promises to one another, and eventually signed our wedding certificate in the meeting for worship. Other people spoke and gave vocal ministry to the worship and so it was … I think folks who weren’t familiar with Quaker norms probably found it weird that there was no photography during the service. There was no picture of us actually standing at the altar or something like that. That doesn’t exist.

Mackenzie: Was there an altar?

Micah: There was not an altar. The closest thing to an altar was there was a facing bench.

Mackenzie: Okay.

Micah: So there’s no photography. There are, obviously photos of us afterwards, but there’s no photography of the actual wedding service. I think this is really interesting because of course, I mean obviously this is not, this is not an ancient Quaker tradition, because cameras did not …

Mackenzie: Are only about 150 years old.

Micah: Right. And the kind of cameras that you would bring into a service, that you could take live action shots are more recent than that.

Mackenzie: Right.

Micah: Older cameras, you would literally have to pose for long periods of time for them to expose. This is a new issue. One of the reasons I think this issue’s really, really interesting is because Quakers traditionally have never had any kind of issues with recording the content of Quaker meetings for worship. It was very frequent for stenographers to come in and be taking, essentially live action notes of what people were saying in the meeting for worship. We have many sermons that have been recorded from the early periods of Quakerism through the 1800s. We have them because people were sitting there, writing them down as they were happening.

Mackenzie: I’m not sure if it was actually non-controversial. Our friend Chip has a very old book from 1830, with a whole bunch of sermons from, there’s some from Elias Hicks, and there’s some from Stephen Crisp from like the 1600s, and some other people. Archie Ross is in there. But, when he showed me that book, he said that the stenographers were of course, not friends themselves, which I found interesting. That he was saying that basically somebody had come in at a public meeting and done the stenography without permission, and actually I think from what I’ve read of Elias Hicks, that his sermons, that at least the publication of his sermons was without permission.

Micah: That’s interesting. I wonder, I mean I know that Chip, Chip if you’re listening, much respect. I know that Chip knows his stuff. That being said, we have sermons from early. We have sermons from real early.

Mackenzie: Like I said, Stephen Crisp is the 1600s.

Micah: Yeah.

Mackenzie: So I don’t know if that was …

Micah: Again, like I actually, if I wanted to do this podcast right, I should actually do some research. I’m basically going off of what I remember from previous research, but I could easily be wrong on this. But it was my impression that in the early Quaker movement, like, they were constantly passing around stuff that they had preached, in addition to their pamphlets. There was a very rich literary culture that included recorded for that time and place, recorded sermons. All that to say, there may be some ambiguity there.

Mackenzie: Yeah, maybe it was sort of that it was fine and then like, I mean if you’re talking about Elias Hicks and having his sermons recorded, you’re talking about …

Micah: [inaudible 00:06:35]

Mackenzie: Well and you’re talking about the time when there’s the schism and all the fighting.

Micah: Right.

Mackenzie: Then you’re looking at a lot of the problems with these sermons being written down and passed around and who knows, like if somebody’s unscrupulous, that they alter stuff. Or at least that there could be accusations of that. There could be so much, with if you have, if you’re publishing the sermons of people who are on two sides of this big argument, and then like going, well you said on such and so date, and how that could play things.

Micah: To be honest, if I had been Elias Hicks or anybody, in any major figure in one of those controversial periods, I would definitely want there to be a trustworthy transcript of what I said because there must have been so much gossip. Plenty of people were saying, Elias Hicks, denied the divinity of Jesus and all kind of stuff, and Elias Hicks, as far as I know, never said things like that. He may have had fairly, he may have had a particular interpretation of different things.

Mackenzie: Or what divinity is.

Micah: Right. But people were accusing Elias Hicks frequently of denying the divinity of Jesus and as far as I know, that was never his position. If I were Elias Hicks or if I were Gurney or if I were another one of these controversial figures, I would definitely want those transcripts there and accurate. I would want my friends giving …

Mackenzie: To be the ones doing the transcribing.

Micah: To give an accurate transcript of what I was saying, so that I wasn’t misrepresented. But all that being said, it seems like even today I don’t, I mean I think it depends on the time and place. The taboo can be more extreme or less extreme depending on where you’re at. I think maybe in some places they wouldn’t want you to make an audio recording, but in my experience, and I guess in my own personal opinion, and audio recording … So first of all I know, I have seen audio recordings be extensively used, particularly in special meetings for worship. In other words, like at …

Mackenzie: Like business meetings.

Micah: No, no. Not at business meetings, but like at Quaker gatherings or yearly meetings or things like that, where there’s going to be a special meeting for worship with a speaker/preacher that you know is going to preach during that meeting for worship. They’re frequently recorded.

Mackenzie: I know just recently, the Young Quaker podcast out of Britain, which the Young Quaker was the newsletter for their young adults group.

Micah: Young friends?

Mackenzie: No it’s called Young Quaker. That was their newsletter for their young adults group, which, the young adults group is called Young Friends.

Micah: Okay.

Mackenzie: But they recently moved into having a monthly podcast. One recent one they did was they had an audio recording of waiting for worship. Now we’ve said in a previous episode that when you have smaller groups, you can have less vocal ministry than in larger groups. This was a small group, so it’s actually a full hour of “silence” but it’s actually showing that an hour of silence isn’t actually completely silence.

Micah: Sure.

Mackenzie: There’s the people shuffling and breathing and all those sorts of noises. They recorded that and now they’re, Jessica Hubbard Bailey from that podcast is talking to BBC and stuff about it because it’s the first time that there has, that has been broadcast out as a public thing, as far as they know of programming worship.

Oops just double checked. It’s actually a half hour, not an entire hour.

Micah: That’s interesting. That may be true. I know that I, on my iPod which I still have one of those, although I rarely use because I’m mostly listening to streaming these days, but on my iPod on my computer, I actually have a number of meetings for worship, and these are usually ones … In fact I think [inaudible 00:10:47] ones where we knew going in to this meeting for worship that someone was going to speak at length.

To be fair, that was every meeting for worship prior to say 1900 for sure. We all went into meetings for worship knowing, oh yes. This person or these people are probably going to give us extended sermons. I think something unique about modern Quakerism, particularly in the liberal branch, but also in the conservative branch, is that we genuinely go in not knowing if anyone’s going to speak at all. Whereas like previously we really did know it.

Maybe sometimes they wouldn’t. There are stories of Quaker ministers who like, they would not speak because God didn’t give them words because they knew, they could sense that the people were there for entertainment, so they weren’t going to give them what they wanted, that kind of thing. But in general you knew that certain people were going to speak, like almost certainly.

Mackenzie: Or you, because we’ve talked before about recording ministers and that has traditionally meant, you knew that, especially when you have like bigger … A lot of meetings used to be a lot bigger too. You knew there were a dozen people there who tended to have messages. Like that was their gift, so between a dozen of them, somebody’s probably going to end up saying something.

Micah: But I guess in particular, with, when ministers traveled, it was generally expected … Like today, I’ve traveled extensively in the ministry and there’s really no expectation necessarily that I’m going to speak during the meeting for worship. I may. I often might, but there’s no expectation that oh yes, Micah’s here as a traveling minister. Therefore, he’s going to give us a 30 minute sermon for the day, right? Whereas in the old days people would be very surprised, it was of note if they were silent, right?

Mackenzie: Like a guest preacher.

Micah: Exactly. So I guess, I think the reason we’re off on this tangent about like extended speaking in worship and expectations about that, is just that I think that the recordings that I’ve listened to, and have listened to repeatedly because some of them were very, very good, all came at times when we knew someone was going to speak.

I don’t think we’ve … A normal Quaker community meeting for worship on a Sunday morning, I don’t know that they’re ever recorded, but the special ones, where we know that we’ve got essentially a guest preacher, are fairly frequently recorded. I know the North Carolina yearly meeting, conservative has recorded one sermon [inaudible 00:13:37] one by Carl Magruder, from I forget. From sometime in the 2000s, and it’s a very good sermon, and he spoke it extemporaneously out of silence, but they recorded it because they knew he was going to talk.

I think of, I’ve listened repeatedly, dozens of times to sermons from the World Gathering of Young Friends, which was an event that really changed my life. Some of those sermons were very, a few of those sermons were extremely impactful on my trajectory. I’ve listened to them over and over again, and I’m very grateful they were recorded because there was so much there, that I’ve listened to these sermons over the years, I find new things in them.

I actually, I think that recording, whether it’s through transcription or whether it’s through audio recording, sort of what I would call passive recording, I think is very much both, for what it’s worth, both within the tradition and valuable, because there’s a lot of, especially sort of in these invited speaker situations. There’s often very, very valuable content that’s worth being re-experienced.

Mackenzie: I think one reason, I think one very significant reason why audio recording is not, remains taboo in regular meetings is because of the chilling speech effect. There are plenty of people who when they stand to speak in meeting, they are clearly very nervous because they are speaking in front of a bunch of people and this is kind of nerve wracking. So if you add in, oh, and also we’re recording everything you say, and we’re going to stick this on the internet later, well, then … Nope, nope. Not standing. Nope. Nope. Cannot talk.

Micah: To be honest I think that recording your average local Quaker meeting Sunday morning meeting for worship every Sunday and putting out would be extremely boring. I think that it is significant that when stenographers regularly went to Quaker meetings for worship it was because there was preaching and there was preaching by people who were very good preachers and they knew there was going to be quality and interesting content. I think it’s not, it’s not insignificant today when we do audio records, I mean it’s because Carl Magruder’s speaking. Colin Saxon’s speaking. [inaudible 00:16:00] Casper is speaking, whoever it is. We know these are like significant people. They’re going to give us something they’ve prepared and it’s significant and of weight.

Mackenzie: Prepared.

Micah: Oh yeah. And I mean like, I think of Carl Magruder’s talk. I mean he, Carl, if you’re listening, come on and contradict me on this, but your sermon at North Carolina yearly meeting conservative, I heard it to be very prepared. Now it was extemporaneous, but you prayed about it. You thought about it. You put a lot of energy into crafting it in your mind and in your heart before the day. This was a prepared sermon. It just happened to be extemporaneous, which is a powerful style that I think Quakers do very well.

Mackenzie: Yeah. Sometimes you hear somebody say, I’ve had this concern that’s laid on me for days or weeks or months, and then they talk about the thing that has been weighing down on them. It’s not a new concern that arrived three minutes ago.

Micah: I think, I feel like, we’re getting really off course here, but this is very interesting. I think that a real weakness in Quakerism, it’s a weakness that comes from our strength. It’s a shadow, or a weakness in Quakerism is that we are so interested in this sort of immediate inspiration, like in the moment inspiration, like I just got this from God, that our messages in the normal meeting for worship, right, why would you record it because it’s so boring, to listen to later.

Our messages end up being one to three minutes long, because we really did just get it. In other words, in our regular meetings for worship, we almost end up like habitually experiencing seeds rather than trees. I think seeds are good but it might be good to experience some trees from time to time too, and trees take time to grow.

Mackenzie: I think that involves a fundamental misunderstanding of the word immediate. Because people, because okay, language changes, right? 500 years ago, if someone looked at something and said, “Oh that’s so artificial,” what they would have meant was that is so artistic. There’s a lot of skill. It’s really artful. Now, it means that is so fake.

Similarly, immediate has changed meaning. Now we think of immediate as meaning right now, and so the immediate promptings of the Spirit mean it has just happened a moment ago, but 300 years ago, when George Fox and Edward Burrow [inaudible 00:18:33] were writing about the immediate promptings of the Spirit, they were meaning without intermediary. It’s direct. Anytime you see one of the early friends say immediate, substitute in the word direct, and you’ll get what they actually mean.

Micah: Yeah. I think there’s, so … I think you’re right, that the word has changed. I think that without intermediary is not quite the right sense because of course, early friends and friends until very recently all professed that the intermediary is Jesus.

Mackenzie: But no human intermediary, because they were talking about immediate as in without having a priest mediating for you.

Micah: Yes. Yes. I think that’s right. But so, one other thing that I sort of wanted to, before … The reason we decided to record this, we’re sort of going off script and doing a podcast one something we find interesting rather than it being in the book necessarily. We’re following the guidance of our inner lights, whatever that means.

I was interested by the reason that the sort of passive audio recording or passive stenography seems like in general it’s been okay. That really, some communities might extend the taboo to passive recording, but in general we tend to think it’s okay. Yet, for someone like, for example, beholding, to be upholding a camera or a video recording device would not be acceptable in almost any circumstance. What’s the difference there?

I think at least for me, and maybe for others, maybe this is the reason, but for me I think the reason that this kind of recording, like sort of active recording or photography is not generally acceptable, is that with the passive recording, you are sort of letting it run. Like whatever happens, the device or in the case of stenography, the stenographer is sort of sitting quietly taking notes.

Mackenzie: Oh we should probably note that back when stenographers were doing this, stenography meant shorthand. It did not mean the little clacky keyboard that you see in the courtroom.

Micah: Right. This was sort of, this was something that, especially today in the day of audio recording. This was something like we turn on the recorder at the beginning of the meeting, and after that, no one thinks about it whatsoever for the rest of the time. It’s just there. Especially audio recording, none of us is put in the position of being the observer. The observer is an inanimate object that we later reference, right?

But in the case of actually like actively taking photographs or active video recording or something like that, you have an operator, and you have someone who in effect is in the space, making decisions about the moments they want to capture and about angles and all those sort of things, and in the case of photographers in particular, moving around the space and lining shots up.

Not only is this sort of disruptive in a superficial way, of like oh I wish that photographer weren’t moving around because they’re distracting me. That may be a part of it, but I don’t think that’s why there’s a taboo. I think the taboo comes from the fact that in meeting for worship, I think we’re going for a number of things in meeting for worship. I think it’s a mistake to say meeting for worship is about just one thing but I think one of the things that we’re going for in meeting for worship is a unitive experience.

I think in the most powerful meetings for worship, there is an experience of oneness and unity and a diminishing or a weakening of individual consciousness into a group consciousness. It’s difficult for that to happen if one or more people in the group is actively taking the role of a third party observer. There’s no room for sort of a detached observer in the meeting for worship. It diminishes what’s happening in meeting for worship if someone is watching as a third party.

Mackenzie: As opposed to participating.

Micah: As opposed to participating.

Mackenzie: I’ve wondered if this is why you don’t see a lot of meetings that have a sign language interpreter. Because well, so like, so for a while one of my friends was attending Friends Meeting Washington, and she’s deaf. From her, I learned some rudimentary signs. I mean, I basically, I sign in English word order, so it’s kind of a pigeon. It’s pigeon sign English, but I would interpret for her during meeting and that was fine. I was participating in meeting for worship as well, but I wonder if meetings are maybe hesitant to hire a sign language interpreter because that person would then not be participating in the worship, just doing the translation?

Micah: I mean, not to be too cynical, but I also just wonder if like …

Mackenzie: Money.

Micah: We don’t want to pay for it.

Mackenzie: What I have seen at Pittsburgh Friends Meeting, last time I visited is that they now have one corner of the room where they have a really big screen for a computer and there’s sort of a keyboard and they open up, open up a text editor and set it to really large font, and somebody’s sitting there and types up the messages as they’re happening. Anybody who’s on that side of the room can read the messages.

Micah: I saw that, I think at the 2008 Friends United Meeting, triennial gathering. They had something like that.

Mackenzie: The name for it, in accessibility is CARC. I think it’s computer aided realtime captioning.

Micah: This is actually a real question. One particular case I’m thinking of, I think less than the realtime capturing of English like you just mentioned. I think a real question is interpretation. You mentioned sign language, but I’ve also at the World Gathering of Friends in particular, and I think it happens a lot at FWCC gatherings, you have …

Mackenzie: FUM.

Micah: And FUM. You have simultaneous interpretation. This raises a real question because at the world gathering of Young Friends, I know our speakers were expected to submit their manuscripts and then not go off them because they needed to be interpreted.

Mackenzie: Interesting.

Micah: It was too difficult to do … Simultaneous interpretation is extremely challenging. I see why. They would say we need these manuscripts in advance, so we generally know what you’re saying, so we can prepare and generally be able to translate on the fly without insane levels of competence. There’s a reason. It is a profession to do simultaneous interpretation for things that need to be appropriately translated, right? You don’t need a gist. You need to actually know what’s being said.

Mackenzie: Right. And I know my knowledge of sign language is not great, but when I was interpreting for my friend, that there would be points where I would just have to spell out a word for her, because I couldn’t, but when you’re going between English and Spanish or French, or Swahili, you’re not going to be able to, spelling isn’t going to cut it.

Micah: I remember it was significant because most of the speakers did have prepared sermons. I think it was all fine because they generally stuck to the script, which was cool, because when I preached my sermons at the Washington City Church of the Brethren here in DC, I generally stick to the script. I may go off on a tangent for a little bit. I may say some things I didn’t expect I’d say, but if you had this text, you could generally follow what I was saying, so it wasn’t a problem in general.

There was at least one preacher I remembered, Laura Saunders from Philadelphia, who she apologized to the interpreters when she started because she said I don’t have a text and I’m not preaching from a text. On the one hand, her sermon, particularly her first sermon was incredibly impactful to me. It may be the most impactful sermon I have ever heard in terms of developing me as a minister. On the one hand, like she was faithful. On the other hand, maybe she was arrogant because the Spanish speaker probably couldn’t follow what she was saying. Because she was speaking extemporaneously. She was speaking in a very … What’s the word I’m looking for? Very energetic manner. I bet you …

Mackenzie: Oh so possibly too fast for the interpreters to keep up with well.

Micah: Yes. On the one hand, I was deeply moved by particularly her first sermon, and I needed it. On the other hand, you probably couldn’t translate that thing in a way that the Spanish speakers needed. Yeah, that’s another thing too. Translation’s really, really difficult. Yeah, translation’s really, really difficult. That’s something that Muslims think about all the time. Are you really getting the message if someone translates it to you, or do you need to hear it in the original that God gave it in, right?

Anyway, I think translation too is sort of a fraught thing for Friends. Because we really do believe that in ideal circumstances the messages we’re hearing are actually like from God. God is actually speaking words to us, so how do you translate that?

Mackenzie: Actually, back when we started this podcast, somebody asked if there could be a Spanish translation of the podcast, and I was like, neither of us are fluent enough for that. Now that I think about it, now that we’re doing the transcripts then we could …

Micah: I am fluent enough to translate it. I don’t have time and energy.

Mackenzie: Okay.

Micah: I mean, yeah but no if we’re doing transcripts, I would love for us to, if our viewers are donating enough to cover the costs, I would love, I think that would be a great thing to have versions of this in Spanish. I’d also be interested, if any of our listeners is a Spanish speaker, that would be interested in coming on, we could do one of our podcasts in Spanish language. I could with that person. So just putting that out there. It’s not impossible. We could do that once for sure. Yeah, I don’t know where our donations are at. The ability to …

Mackenzie: The current …

Micah: To go into NPR mode here.

Mackenzie: Right.

Micah: Our spring campaign, I don’t know where our donations are at, but if they are at the level where we could afford something like that, I think that could be cool.

Mackenzie: Currently our Patreon is bringing in $38 per episode, which is a few dollars more than how much it costs to transcribe one episode, which so far has meant that I think one or maybe two of the past episodes have also gotten transcribed, because we get to where it’s like, okay, so after three months, we have enough money to do one old one. All right, there we go.

Micah: Okay.

Mackenzie: There’s a little goal on Patreon of hitting $60 so that we can do one old one and the current one each time.

Micah: So basically I think there are really two possibilities here. The first is that one or more people are going to come out of the woodwork and start supporting this podcast significantly on Patreon.

Mackenzie: There’s one person who is really supporting, there’s one person who is giving $25 per episode, so thank you that person.

Micah: Thank you so much to that person. So I think there are really two possibilities here. One is that one or more people are going to come out of the woodwork to be significant supporters through Patreon and then we could afford to hire a translator, to take the transcription that we have and translate that into Spanish, right? We could do that.

The other possibility is there is someone listening or a friend of someone listening who is capable and willing to do that translation, and that would be amazing. If you are that person or you know that person, please get in touch, because we would love to have our transcriptions in Spanish, but Mackenzie and I do not have the resources to do that ourselves.

Mackenzie: I certainly don’t have the skills.

Speaker 1: You can find us on the web at Quakerpodcast.org, as Quaker Podcast on Twitter, Facebook or Patreon and on iTunes.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Email | RSS